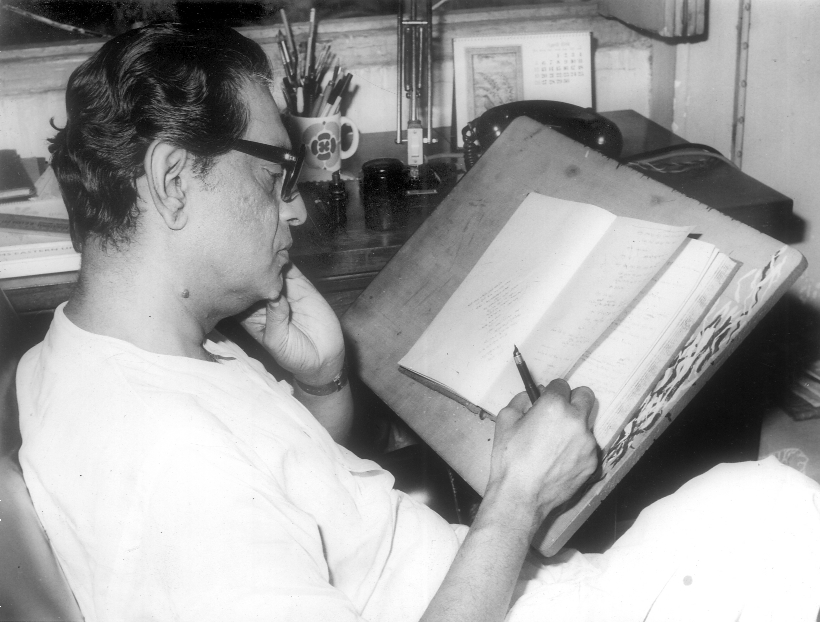

On Satyajit Ray’s centenary, IFFSA Ambassador Anup Singh presents a view from Punjab

ON SATYAJIT RAY’S CENTENARY, IFFSA AMBASSADOR ANUP SINGH PRESENTS A VIEW FROM PUNJAB

Anup Singh

On May 2, India and the world will be celebrating Satyajit Ray’s birth centenary. And here in Punjab, how are we considering celebrating this extraordinary filmmaker? In fact, are we going to? Should we? We might even ask ourselves, why should we? Well, we have to admit to ourselves that there’s no other Indian filmmaker who has managed to safeguard international respect for Indian cinema the way his work has for the past 60 years or so. And not only respect, there’s a deep affection in the hearts of film professionals, writers, scientists, educators, politicians, besides of course ordinary filmgoers.

Then, something that has enchanted me from the very first moment I noticed it in Ray’s cinema: his adroit ability to capture precise particulars. For instance, rain drops as they rebound as scintillations when they hit a surface, or the sense of heat building in a hand lying in a fragment of sunshine on a windowsill. And, you realise that even as these particulars — be they of a village or a specific city — might create a sense of identity, draw a border, Ray always seeks to push and open them towards lively, varied correspondences with the deeper patterns of our world. Identity and borders in Ray do not close, Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World) are not in opposition.

There’s a resplendent affirmation of our earthly life in Ray’s work. There’s a resolve and strength to cherish what the world might revile, and a longing to seek not for us, his audience, but with us, our genuine relationship with our cosmos.

In his own way, Ray’s work is imbued with the quest and questions that we find in the visionary poetry of Guru Nanak or in the poetry of some of our Sufi poets. This should not come as a surprise as Ray connects to Punjab through Rabindranath Tagore. And, of course, a very large number of Ray’s films are based on Tagore’s stories and novels. We know that Tagore travelled with his father to Punjab at the age of 11. They rented a big house on the outskirts of Amritsar and visited the Golden Temple everyday. It seems the young Tagore was mesmerised by Guru Nanak’s Aarti and translated it into Bangla for the first time. We also know that the great actor, Balraj Sahni, had once asked Tagore that while he had written many important anthems for India, why had he not written an anthem for the whole world? Tagore had replied that, in fact, such an anthem had already been written. Not only for the world, but for the entire universe — in the 16th century by Guru Nanak. He was referring to Guru Nanak’s Aarti. Tagore’s poetry, his stories are saturated with Sufi bhakti resonances. While in many ways these resonances emerge in Ray’s narratives, they are even more vibrant in some of his images. These moments are like an epiphany, a heightened, dazzling perception in the trivial aspects of the everyday. They are of fugitive beauty, fading even as you notice them, but somehow they abide in us for the rest of our life.

Guru Nanak’s Aarti has the same incandescence:

“Gagan Mae Thaal Rava

Chanda Deepak Banay

Tarka Mandala Janak Moti

Dhoop Malyanalo Pavan Chavro Karey

Sagal Banray Phulant Jyoti”

(The sky is your platter

The sun and moon are the lamps

The stars in the sky are the pearls

The incense is the fragrance

That the wind propels

All the flora and fauna your flowers)

The invocation brings us a revelation, it opens the framework of our consciousness. The distance between the individual and the cosmos burns away. Early French film theoreticians called such poetic moments in cinema — photogénie. They believed that such a moment defined the very epitome of cinema. It was the very rare film, though, that had these moments. For me, there’s one such moment in Mughal-e-Azam and in Dilip Kumar’s Taraana. In the films of Guru Dutt, such moments take you by surprise, often leaving you with that strange sense of serenity that a desolating insight can bring you.

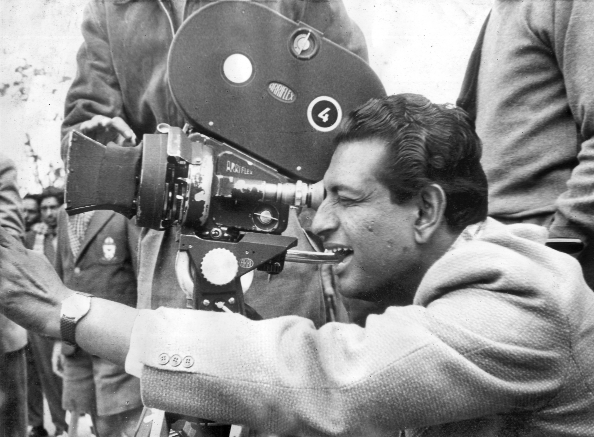

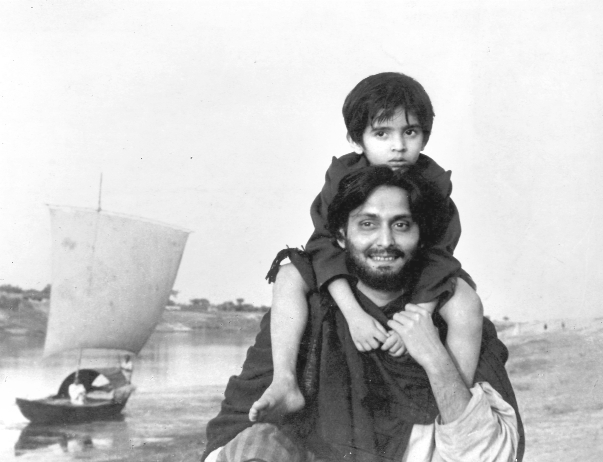

In the works of Satyajit Ray, however, and his peer, Ritwik Ghatak, these moments enrapture us and annihilate us (in the Sufi sense of ‘Fanaa’) in almost all their films. In Ray’s first film, Pather Panchali (Song of the Road), Durga, a girl of about 13, dances in the first monsoon. Apu, her younger brother, watches her from under the protection of a tree. Her hair open, Durga wheels around herself under the vast cloud-covered sky. The rain glitters as it falls and the lake behind her is luminous like a face. Here, the time in the film is suddenly suspended. A young woman takes complete possession of herself and her universe, while the universe seems to forego its indifference and shimmers with her.

It’s no exaggeration when I say there’s no song sequence in Indian cinema that has the bewildering and exhilarating force of life that we see here. The film, the light, rain, landscape and Durga, for a long moment, beat with a rhythm where machine, heart and blood and the vibration of the cosmos are no longer distinguishable. Usually, these wondrous moments are brief. But I would argue that in the sequence where Apu and Durga walk through the long, white-wisped kusha grass and to their first sighting of the steam-clouded train, there’s almost a patterning of such ineffable moments of beauty.

There’s nothing like this in world cinema (all exceptions granted: the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu Monogatari, and in the cinema of Ritwik Ghatak. See especially Ghatak’s song sequence ‘Aeri Dekho, Bhor Bhayi’, in Subarnarekha). Though never with the same haunting quality after Pather Panchali and much more briefly, such moments continue to surface in almost every other of Ray’s next films. Almost all filmmakers are curtailed by budgets and expectations. Ray was too.

After Pather Panchali, he made choices and never returned to the free-flowing, meandering narrative of his first film. His films now moved more and more towards classical story-telling. The relentless forward thrust of classical narration has a great seductive power, but that’s often also its weakness. The play becomes limited to a chain of cause and effect, each action locked to the next, imprisoning us within foreseeable rhythms. The closed flow makes it almost impossible for a moment, an image to surface for itself. For me, Ray’s choice to work within this classical mode heralds a narrowing in his wondrous ability to suggest and evoke. Over time, the struggle in his films between the photogénie and the classical narrative becomes more and more tense. But the tenacious and virtuoso quality of his struggle, his determination to keep seeking those rapturous moments — even within the limitations he had set for himself — is awe-inspiring.

That incorruptibility is what makes us cherish and revere him even today. This complex creative play in his work continues to bring nourishment to one generation after another. In Pather Panchali, he achieved something supremely rare where, at moments, all mediations between the self and phenomena fade away. And, in his later works, the purity of his struggle to keep the heightened life-force alive has helped usher in a range of illumined traditions into Indian cinema today. We have the epiphanic cinema of Amit Dutta, the powerful, socially conscious films of Sanal Kumar Sasidharan. There is the cinema of Chaitanya Tamhane and Gurvinder Singh, who endeavour to hold these two tendencies together, and then those that choose classical story-telling (the mainstream cinema). As filmmakers, as audiences, whatever choices we make, I believe Ray’s cinema shows us that our struggle to live our story on this earth has to be open to discontinuities. His cinema gives us courage to take a pause and, perhaps, that might allow a colour, a face, a tree, a line of a poem to rise before our eyes. And while this moment, this image, affirms its own existence with us as witnesses, it might also transfigure our life.

Satyajit Ray’s films, like Punjab’s visionary texts, aim to transform. They reject nothing and ask of us only that we not evade — with whatever excuses, be it the budget or audience expectations — any such moment that might bring us the opportunity to expand our life. By celebrating Ray, we’re celebrating what is best in us.

-x-

ANUP SINGH

Anup Singh is an internationally renowned writer, film director and teacher of cinema whose feature “Qissa – The Tale of a Lonely Ghost” (2013) premiered at TIFF, where it won the award for “Best Asian Film” (NETPAC). One of the most critically acclaimed films of our times, it has won 15 international awards to date. His next masterpiece, “The Song of Scorpions” (2017), starring Irrfan Khan and Golshifteh Farahani had its world premiere at Locarno Film Festival in front of 8000 people on the world’s largest film screen. The film has won numerous accolades worldwide. His first feature, “The Name of a River” (2001) was awarded the Aravindan Award for best debut filmmaker in India. Currently he is working on his next feature film “Lasya – The Gentle Dance”, an Indo-Swiss co-production which is being shot in the summer of 2021.

Anup Singh was born in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania, East Africa. He studied Literature and Philosophy at Bombay University and Film at the Film & TV Institute of India, from which he graduated in direction in 1986. He now lives & works in Geneva, Switzerland. Anup Singh has taught and lectured on cinema at numerous universities and film schools in the UK, India and Switzerland. He has also written and directed numerous TV projects and consulted for BBC.